An interview with Vedran, bass player with the Dubioza Kolektiv, backstage at The Fleece in Bristol.

The Dubioza Kolektiv are a Balkan-based outfit that have about as much respect for genres as they do borders. They take traditional Balkan folk music and mix it with punk, ska, techno, hip-hop, dub and just about anything that takes their fancy. Constantly evolving, they will have you on your toes in more ways than one. They will keep you guessing which direction they are going next and have you dancing to their infectious upbeat vibes.

With the memories of the collapse of Yugoslavia still fresh, they formed in 2003 and featured band members from across the nations that, only a few years earlier, had been at war with each other. Their self-entitled first album “Dubioza Kolektiv” was released in 2004 and was instantly met with an enthusiasm not seen on the Bosnian scene since before the war. They quickly gained attention outside of the Balkans and were soon working with the likes of Benjamin Zephania and Faith No More’s Bill Gould; the latter picking up the fifth album, ‘Wild, Wild East’ for his label Koolarrow Records and introducing Dubioza Kolektiv to the international stage with worldwide distribution.

They have done thousands of gigs all over the world, been downloaded hundreds of thousands of times and been viewed on YouTube millions of times. Not bad for a band who sing most of their songs in a language many of their fans don’t understand. But, as a friend from Macedonia recently pointed out, ‘There are many punk bands that sing in English but you don’t have a clue what they are singing about’. Or to misquote the Propellerheads, ‘Some people won’t dance if they don’t know what they are singing. Why ask your head, it’s your hips that are swinging’. In other words, good music knows no language barriers.

The band arrive in the UK at a time of heightened tensions across the UK, with the far-right taking advantage of ignorance and fear about ‘Johnny Foreigner’, with migrants being scapegoated for the failures of capitalism.

As the band are loading their gear into Bristol’s Fleece, the far-right are holding an anti-migration protest just across the city on College Green. But this is Bristol, they are outnumbered by anti-racist protestors by 10-1. If there is a city anywhere in the UK that is receptive to progressive, multi-lingual, cross-cultural, international party music, it is Bristol.

We arrive at The Fleece just in time to catch the end of the band’s soundcheck and soon head upstairs for a chat with Vedran. An original member of the band, he is intelligent, culturally aware, speaks near perfect English and looks like someone who has spent the last two decades doing an aerobic workout on stage most nights.

Vedran Mujagić was born in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He studied at the Architecture Faculty, University of Sarajevo and Graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts, University of Sarajevo. 1998-2002. He was a member of the band Adi Lukovac & Ornamenti, pioneers of Bosnian electronic music. As well as playing bass guitar, he is in charge of art direction and Dubioza Kolektiv’s visual identity

We start with a light hearted icebreaker.

If Dubioza Collective were a car, what sort of car would it be?

That’s a beautiful question. Probably, we would be some Eastern European made… Trabant or something. Something very durable, but with Eastern European charm, I guess. Maybe with some new hybrid motor.

Balkan music is not unique in the UK. In the 1990s a ‘Balkan Beat’ scene originated in Berlin and soon spread to London with several compilation CDs being released on the back of it, although much of that was DJ focussed. The Balkan sound has never really troubled the mainstream and is still slightly novel in the UK. But what about back in the Balkans? Do people still listen to traditional Balkan music, or is it more western music?

They do. It depends on the generation. The new generation have their own interpretations of folk-influenced pop music, which is very popular, probably the biggest thing back there. Everyone still listens to traditional music, and there are a lot of artists in the world music scene, traditional singers and interpreters of folk music that are doing it in their own way.

But there are all kinds of versions in between. You will find everything from trap-folk to really traditional stuff. So everything is there.

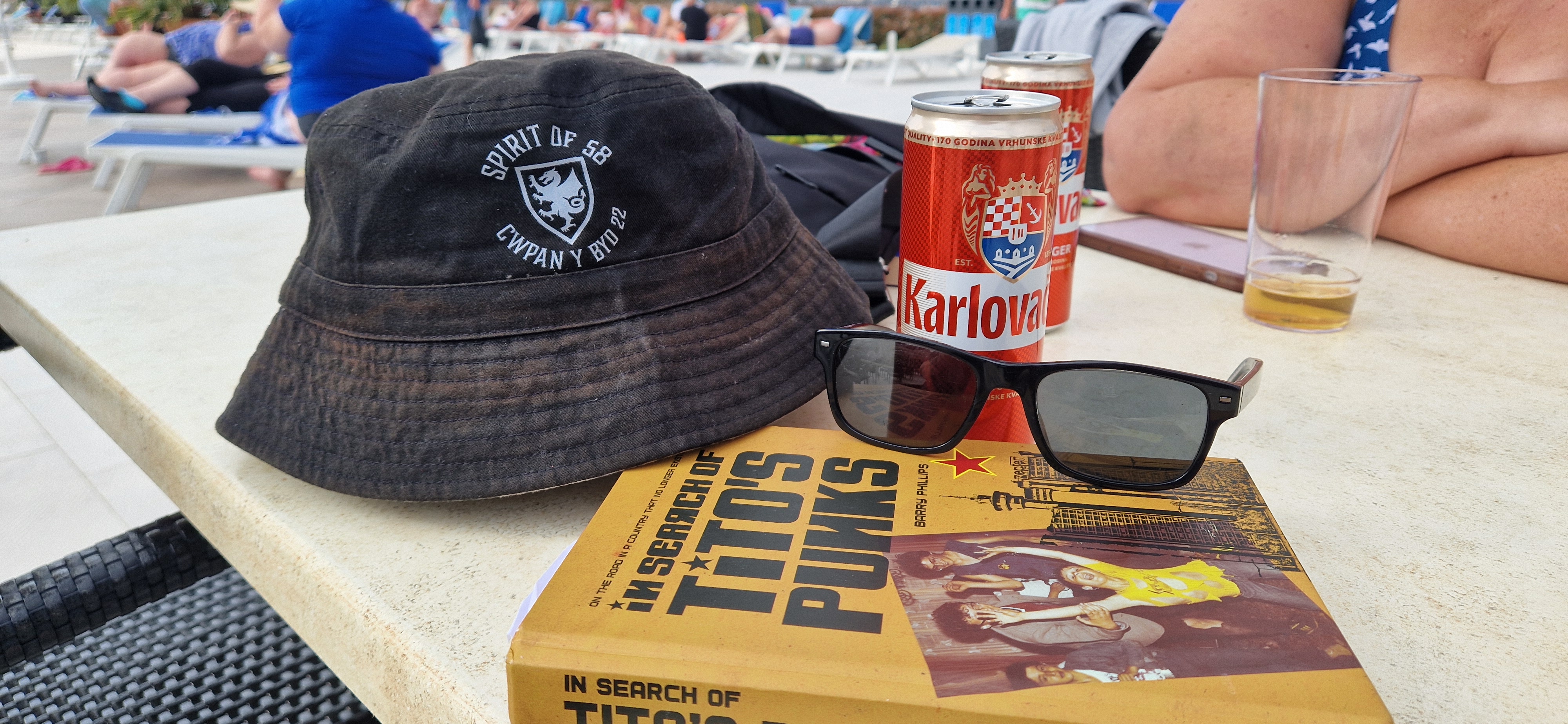

There is a book about the former Yugoslavia, Barry Phillips’ ‘In Search of Tito’s Punks’. In that, it says that back in the day, there were four main countries for producing punk rock. That would have been the UK, America, Australia, and Yugoslavia. We recently met up with the Naked Mountain Collective in Macedonia who run a DIY label that has an eclectic output, but there is definily a heavy leaning towards the punk attitude and post punk sound. Why do you think the former Yugoslavia in particular has been keeping the punk rock flag flying?

I guess out of all of these countries, let’s call it the Eastern Bloc, Yugoslavia was the liberal version of that. Because when you talk about Eastern Europe during the Cold War, you always talk about the Iron Curtain, and Yugoslavia was not part of that. We were an unaligned country.

We were outside of the Warsaw Pact, outside of NATO, so we were somewhere stuck in between. And somehow, especially after the 1968 student revolt, the authorities realized that maybe it’s not the best thing to suppress youth culture. So they allowed some imports from the West.

A lot of music came in that moment from England, from the US. And also, I guess, it was just the right moment in time that enough time passed after the Second World War, and enough wealth being created, so that the people could start really thinking about doing some serious art, in the 70s especially, and onwards.

We were kids when all of this happened. Some of us were being born in that moment. So we cannot tell you first hand, but we all grew up on the heritage of that 70s new wave punk scene, which was very progressive. When you compare it to what happened in the UK at that moment, you can really see that it happened at the same time. It wasn’t lagging five years behind, it was happening in the same time. The influences were there, of course, but the Yugoslav punk and Yugoslav new wave had its own flavour.

And what we discovered later is that it also had second-hand life, because this wave of bands and artists influenced the Eastern European scene further. Somehow the Polish, Bulgarian and Czech authorities saw Yugoslavia as not the evil West, but somehow a socialist little brother. And then some arts and bands were allowed to be imported there and distributed to this Eastern bloc via that direction.

So when we started touring Poland, for example, we realised how many people from Poland, and you wouldn’t make that connection otherwise, how many bands were influenced, how many people listened to ex-Yugoslav new wave and punk music and rock music in general in that era.

And it’s somehow extended to this day. It’s very strange. Bulgarians listen to a lot of rock and roll, punk, new music from ex-Yugoslavian countries, but the other way around is not the case. Not many Romanian or Bulgarian bands are listened to in ex-Yugoslavia. It’s a pity for us.

The scene is alive and well. It’s not commercially successful, but I think the entire scene has to be reinvented in a way, and probably the only way is the DIY principle, because with all of these monopolies by ticket services, the prices of the tickets are going crazy. I think people will revolt against that, because you cannot afford to go to ten concerts a month like before. Now you have to choose one. On the other hand, you have a lot of these small venues and small bands that are willing to do it for the sake of music, not just for the sake of money, and then I guess people will pivot to that direction in one moment. I really hope that it’s going to happen.

In the UK you had bands like Crass and Conflict, and in America you had Dead Kennedys, for instance, and Black Flag, they were all trying to bring down the system in their own little way. But I read an interesting quote from a band called Youth of Today, where they said the ‘Yugoslav punk is not against the system, they’re against anomalies in the system’, so they’re just trying to change little bits of what they see as wrong. Would you say that’s the case?

It’s hard to generalise. There were more and less open expressions of the idea of how the system should be changed, or what should be the new system. But I wouldn’t say that it was completely liberal, like do whatever you want, say whatever you want, and we’ll publish you. Because most of the record labels were state-owned and had some level of control.

Of course, there were some small underground labels that did this DIY prints and cassettes in that moment, but the bigger bands still had to try to be subversive undercover, without disturbing everything. Also, I don’t think that in that moment, at least how I interpreted it forty years later, those bands were not completely disgusted with the system.

As you said, they believed in this… or put it the other way. Most of these bands that you’ve spoken about from the UK, they would probably be much happier in socialist Yugoslavia of that time than in capitalist West. But their ideals were more aligned with what we had, at least as an idea of society, that were more egalitarian, more equal, and more friendly towards working class and everything. So the rebellion was not against the system as it was, but more, as you said, against anomalies of the system.

Because, of course, in one moment they defined it as red bourgeoisie, the ruling class that somehow got too rich, basically, while still fighting for what they preached.

I understand most of the band are from Bosnia, but you are not all from Bosnia. What other contras are represented in the band?

We have people from all around. The guitarist is from Slovenia, the saxophone player is from Serbia, and the rest are from Bosnia

Nationalism and xenophobia is on the rise in the UK hiding under the guise of ‘patriotism’. But you only need to look at the recent history of the Balkans to see where ‘patriotism’ can lead. Even several decades on, when you mention Bosnia or Serbia to someone in the UK, they automatically start thinking about the war. Do Balkan people now get on with each other, or does nationalist rivalry still lurk there?

I mean, people get along well, but, of course, politicians are still using these tensions basically as a populist tool to stay in power and to talk about other things rather than economy or what’s important. I guess that kind of animosity you will find even inside the UK. It’s that kind of Scottish, Welsh, British, whatever. It’s just a matter of how big it is and how violent it is in the moment.

Do you think music can act as a unifying force to bring people from different communities and different countries together?

Obviously, it can work that way. We are not idealistic. We don’t think that music changes the world and all this hippie belief that it will be all better after a few songs. But it really does help. We saw it after the wars in Yugoslavia in the late 90s. The first thing that started circulating were the bands and movies. The pop culture, because it’s the same language territory, or similar, the nationalists would say it’s not the same language, but basically we all understand each other, all the former countries.

We all share the common, at least pop cultural heritage. Our generation all grew up on the same TV shows, same bands, listening to the same stuff. It’s very easy to understand each other and to be on the same level. I guess music, in our case, in Balkan case, was a very strong unifying force.

There’s quite a few of you in the band, and obviously you all have your own influences from the past. Is there any one particular, or any two particular people that write most of the music, or do you all mix in and bring your own influences into it?

We do, but our keyboard player and DJ is a producer. He writes most of the music. Lyrics, it depends on the idea, but it’s not a fixed way of doing things. Sometimes it’s a group effort, sometimes it’s one-man effort. It changes from album to album.

When something becomes popular, often a lot of other bands will follow in a similar vein. For instance, a few years ago now, I discovered a Mongolian folk metal band called The Hu. And then all of a sudden, there was lots of Mongolian folk metal bands. Do you find that all of a sudden, you’re seeing lots of other Balkan bands doing similar stuff to what you were doing?

There are. There are bands that probably followed our example. Not necessarily musically, but more as they were encouraged by the things that we did, the festivals we played, that they somehow realized suddenly that there is a way to go outside the region and to appeal to wider audiences in the world.

As with any wave, especially in world music, you have waves, you have Cuban waves, you have Balkan waves, you have North African, it’s kind of Middle Eastern, Pakistan, it comes and goes. And all the festivals are booking one type of the band for a year or two and then they go to something else.

Some people try to jump to that wagon with more traditional stuff, and they’re with more or less success, but for a couple of years they did. Balkan music was a huge thing in at least these world music circles, but what we do is less traditional. We almost never play world music festivals.

We often play festivals like Boomtown, you will find us more there than at some world music festivals, because people cannot put us in a niche of a genre because it’s eclectic, I guess. What you mentioned, this Macedonian scene, they have amazing folk music and very interesting, also complicated with all these irregular rhythms and everything. You’ll find a punk band from Macedonia that has this influence, you can hear this influence in their sound.

So I guess in that way, maybe people are now a little less afraid to combine folk music with other genres. Because before it was like no-go zone, it was like a straight line between rock’n’roll and folk. You wouldn’t mix those two.

In the 70s and 80s, you would not find a lot of bands on that left field of alternative music. They would probably sound more like a band from the UK than a band from ex-Yugoslavia. But now these borders shift, people are not afraid, or not ashamed, let’s say, to put this type of sound into the mix.

So I guess it’s more interesting now. Because for us, we always thought, why would Glastonbury or Boomtown or anybody book another band that sounds exactly like somebody from London? Why would you bring us from Bosnia to sound like something you have at home? It totally doesn’t make sense. You’re just copying, trying to sound like something that you are not.

Even if you like that kind of music, if you’re not bringing something new to the scene, then why would anybody be interested? Okay, locally you can do it, of course. You can play in your city, country, whatever. Play Britrock, Britpop, or whatever.

But let’s say, bluntly, as an export, it doesn’t make sense. Why would anybody book you?

Dubioza Kolektiv performing MPFree during lockdown.

I know that most of your music is available to download for free on Bandcamp and other places. Do you find that you still manage to sell vinyl and CDs?

You would be surprised. It’s something that we chose early. Before we even had any kind of record deal. When internet became strong enough to support downloads and hosting stuff for free, we were there. We jumped into that wagon, because that was a dream come true for us. To share your music with a large number of people in real time. It’s something that, in that moment, traditional music distribution couldn’t, at least in our region, because the music industry was not strong before and after the war was devastated. It was almost non-existing. So we struggled, obviously, to get our music to people. So, when internet became a thing, that was our thing.

So, we started from the beginning, and when some of these albums really exploded with numbers that we ourselves couldn’t believe that are possible. The Apsurdistan album from almost fifteen years ago was downloaded 300,000 times. It was a big number for our region.

Then, suddenly, the record labels became interested. It was funny, because that album was already released as a free download, and the record label said, we want to release it as a CD. Why would you do it? They said “Trust me, we know why we would do it”.

Then, it was the best-selling CD of that month or something. Because people, even if they had it for free, they still wanted to show support or to have a physical manifestation of it somewhere on a shelf. So, now it’s the same with vinyl and with CDs. People still buy it, not as a necessity, but as a sign of support. I think it’s fair. So, you just give all the options.

You have streaming services, you have free download, you have Bandcamp, you have physical releases. Whatever is good for you is good for us. Just a couple more.

Music – Dubioza Kolektiv – download their back catalogue for free – legitimately

I noticed you’ve done quite a few collaborations with people like Manu Cho and Benji Webb, who is actually from my neck of the woods, South Wales. Do you have to go looking for these people to collaborate with, or do they come to you, or does a record label sort them out?

Most of these collaborations were almost an accident. Just something that happened organically. You meet bands at festivals, you talk to them, then you have some idea for a song, and then you realise it would be good to have that guy. You try, you connect with them, and if it clicks, it clicks. You don’t push it, you don’t prearrange it, and that’s the only way for us that makes sense. If it’s the other way around, then it’s kind of artificial, and then most of the time it doesn’t work.

The album #Fakenews features collaborations with Manu Chao and Earl Sixteen

You’ve travelled quite a lot, so which would you say is your favourite country to play in?

That’s a hard question. We really enjoy travelling, and we’ve been to Australia, to India, to New Zealand, to South America, and for us it’s more about where we haven’t played and want to play.

South America is very good, Mexico and also Colombia and Chile are good. The energy and the mentality of the people is very compatible with Balkan energy and mentality, so we always have great reception there. It’s a great thing.

I would say that we’re enjoying touring in Britain. I explained that to somebody a couple of days ago. The good thing about the UK is that the humour and the way people understand the jokes is 100% compatible to Balkan, because we all share this dark humour.

Probably that was the reason why the British TV comedy shows were the biggest outside of the UK. They were biggest in ex-Yugoslavia, and we were lucky to see them without overdubs. We’d just seen them in English with subtitles. So I grew up watching Monty Python and Only Fools and Horses and all these shows. You wouldn’t believe how many cultural references are in popular culture of ex-Yugoslavia that kind of had this as an influence. Both music, TV, movies, more than US, for example. A lot more.

So for us, it’s always funny. Last night, we tell some jokes, we have this funny concert intro, and people laugh. You don’t have to explain. In some other countries, jokes work a little bit less. Because it’s not the same. There, you have to adapt.

You have to go around and find other ways to get to the people. But here, it’s just like we’re in Bosnia. We talk in English. Same jokes, same things work in both countries. So for us, it’s always fun to be here.

Can we expect a new album anytime soon?

Actually, yes. There will be a ton of new music coming out. But we’re not sure if it’s going to be albums or if it’s going to be a bunch of singles, a bunch of EPs. We do songs now, currently.

We have a bunch of songs in Bosnian, a bunch of songs in English, a bunch of songs in Spanish. So probably… We’ll see if we’re going to release three separate releases, if it’s going to be just a bunch of songs going out on all of these platforms, one by one.

The music industry is changing, so we’re also trying to figure out what works the best. Because nowadays, when you put an album out, the algorithm and streaming platforms just somehow give space to one or two songs, and the rest are kind of hidden somewhere behind this algorithm. Somehow, it makes more sense to put more singles and just refresh your catalogue every couple of weeks or months. We’ll all probably transition to that kind of releasing new music.

At this point we call an end to the chat. The band get into character and we head down the pub.

When the doors open, I head down the front to get prime spot to take photographs. I last a few numbers but it soon gets quite hectic with lots of energy and bouncing. These guys really are like a Balkan workout to keep you fit.

There are, of course, numbers in English, but a lot of them are sung in Bosnian. At one point the band carry out a ‘hands up if you are from’ type survey. It would appear that quite a few East Europeans have turned out for tonight. And Bristol welcomes them all with open arms. As they should.

As I walk out into the autumn night at the end of the gig an excited stranger hugs me and says “Wasn’t that just the best gig of the year?” And you know what, it’s been a great year for gigs, but he might just be right.

Dubioza Kolektiv – Official web site

Music | Dubioza kolektiv – Bandcamp link

Music – Dubioza Kolektiv – link to download all the bands music for free – legitimately – honest.