A snapshot of life in Qatar in the early twentieth century.

This is a well written and eminently readable look at Qatar in the run up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The author hasn’t restricted himself to the World Cup, he looks at all aspects of life in the country, from falconry to fast cars, from alcohol to cricket to, inevitably, the working conditions of the migrants building the infrastructure of this rapidly growing country. Including the football stadiums.

This is a well written and eminently readable look at Qatar in the run up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The author hasn’t restricted himself to the World Cup, he looks at all aspects of life in the country, from falconry to fast cars, from alcohol to cricket to, inevitably, the working conditions of the migrants building the infrastructure of this rapidly growing country. Including the football stadiums.

It is all written from a personal perspective, he visits the country and meets with the people who live and work there. He tries to drill down into the psyche of Qatari nationals, but finds them incredibly difficult to penetrate, so most of the book focuses on the lives of the migrants working there. It combines interviews, personal thoughts and well researched facts.

In 1970, Qatar, which is the size of Devon and Cornwall, had a population of 47,000. Today it has a population of 2.8 million. A growth prompted by the discovery and exploitation of oil. Of that 2.8 million though, 86% of the population are migrants. Given most of those migrants are men, 76% of the population are male.

Qatari citizens are very much in the minority, but still dominate and have significant privileges over others. There is a very pronounced pecking order in society. Qataris, western European and Americans, other Arabic nationals, Africans, Asians. There is very little mixing between these ethnic groups and Qatari Citizens often look down on all others with contempt.

The country is rich. Really rich. It has the fourth highest GDP per capita in the world. Indigenous citizens do not pay tax and do not pay for electricity or water, such is the wealth of the country. This generosity from the state means there is very little demand for democracy in this autocratic monarchy. Yet there are still high levels of debt. Not because the Qataris are poorly paid, but because consumerism is rampant, with people wanting the latest gadgets.

It is also hot. Very hot. Between June and September, the temperature never drops below 30 degrees Celsius. Even at night. In most years they only have 2cm of rain per annum, with an average of nine days of rain each year. As a result, it has no rivers or lakes. The only local source of drinking water is desalinated sea water.

For a non Qarati to get a job in the country they have to get a local ‘sponsor’. It is known as the ‘kafala’ system, which had originally been introduced by the British and was intended to make locals responsible for migrant workers and ensure their welfare. To a certain extent that is still the case – for well paid technical and financial jobs for ‘western’ migrants in the oil industry and other high earning services.

However, for the low paid workers, they have to pay a fee to get sponsorship, something they often have to go into debt for. When they arrive, they often find they are not being paid what they were promised and often have to wait months to be paid. Given that most of them are there to earn money to send back to their families, this causes problems back home.

Many of them have their passports confiscated so cannot leave the country without permission of their sponsor. They are required to carry ID at all times, but many employers withhold this, resulting in workers having to stay within the compound they are working in to avoid arrest. The sponsor system also means they cannot change employer unless their sponsor agrees, and very often they do not, resulting in workers being trapped in jobs they don’t want, not getting decent pay, unable to live normal lives and not able to leave the country.

The working conditions can be poor, with little health and safety and often having to work in unbearable heat. Needless to say, many die. Exactly how many die is difficult to calculate, because the recording of causes of death is slack, to say the least. And autopsies are only allowed in very special circumstances. As a result, many work-related deaths are often categorised as ‘natural causes’. Many are reported as ‘heart failure’, but as the book says, ultimately, we all die of heart failure, it is the cause of that failure that is important. Is it just a dodgy ticker or is it hard graft in fifty degree heat?

The Guardian ran a headline that six thousand five hundred migrant workers died in the ten years between the world cup being awarded and 2020. This is an interesting figure, but does not really tell us much. Only thirty-seven of them were actually working on the stadiums, many more were working on the infrastructure to accommodate the word cup and some were totally unrelated. It is difficult to work out what is what. Not only are migrants building the new Qatar, they are cleaning it, cooking food, teaching and looking after children in it.

The infrastructure includes a lot of hotels, but that does not necessarily mean there are lot of hotels available for fans. Because drinking is illegal in the country, except in hotels, a lot of wealthy ‘ex-pats’ in high paid industries, such as oil, choose to live in hotels, so they don’t have to go out for a drink and don’t need to worry about being arrested for being drunk in the street.

Although alcohol is illegal, it doesn’t mean no one drinks. The book looks at bootlegging Qatar style, with people going blind from drinking moonshine.

The fact that the World Cup is even being played in Qatar is a source of much controversy. Allegations of corruption abound. This book does not go into much detail on this – for that check out the Sunday Times Insight book – but the author does look at football in the country.

Although it is almost impossible to gain Qatari citizenship, FIFA had to change its rules regarding qualification when in 2004 Qatar wanted to field three Brazilian born players who had not set foot in the country.

In 2004 the Aspire sports academy was set up, with the aim of pump priming their sporting achievements. The football academy is run by well-respected European coaches and money has been pumped into raising standards. As a result, the national team has climbed up the world rankings.

In 2014, the Qatar U-19 National Football Team, composed solely of past or current Aspire Academy student-athletes, won the 38th edition of the AFC U-19 Championship in Myanmar, for the first time in Qatar’s history. With the same Aspire players, the senior side managed to conquer the nation’s first ever AFC Asian Cup in 2019 edition. The future of the academy post world cup is in doubt though.

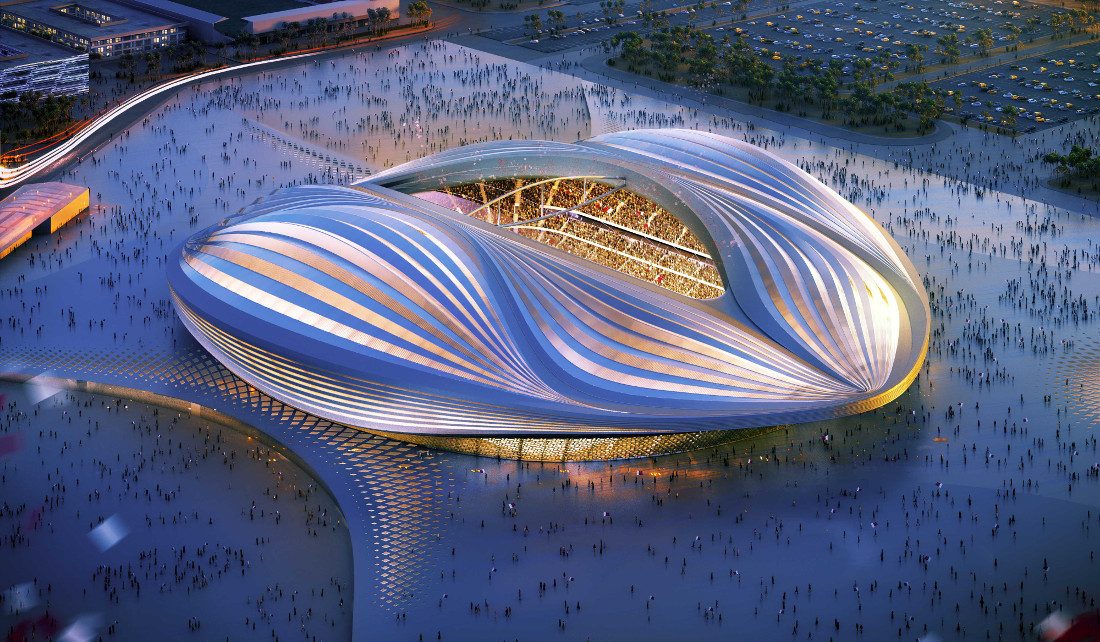

The world cup will see seven new state-of-the-art stadiums built, which in any other country would be a brilliant legacy. But in Qatar, whilst they do have several professional clubs, the teams are mostly made up of foreign players and the small crowds that turn up, tend to be dominated by western ex-pats, rather that Qataris themselves.

These new stadiums will allegedly be carbon neutral, with solar panels powering the air conditioning required to make them fit to play football in. Even in November. Yes, air-conditioned stadiums. Although the carbon neutral claim does not take into account the carbon footprint of actually building the stadium, just the running of it.

With many of the migrants working on the stadiums coming from India, Cricket is actually far more popular than football, but the facilities are incredibly basic. Workers often have to play on concrete wickets on bits of waste ground, using home made bats. The author spends time in the company of an entrepreneur who has set up a business providing cricket equipment.

He also spends time with a worker who had a horrific accident at work and was sent home as lockdown hit. He was told the company had shut down as a result of Covid, making him redundant and therefore not eligible for company help with medical expenses – although in reality the company was still operating.

This in-depth book is not just about the controversies that have been highlighted since the awarding of the World Cup, it is about life in the country in general. looks at many other aspects of life in the country. From the lack of workers’ rights, religion and attitudes towards marriage, fidelity and homosexuality, to food, family life, obsessions with cars, the hospital system, popular music and attitudes towards global warming.

Whilst the country has come in for a lot of criticism of late, a lot of that is down to the spotlight being shone on it since the awarding for the World Cup. Many countries in the region have similar problems, but they aint holding the World Cup so don’t get the same scrutiny. The result of all this interest has led to, in theory, new legislation being brought in to protect workers, but in practice, there is little sign of this actually making any difference.

The book is well written and easy to read. If you are considering going to Qatar for the world cup, I thoroughly recommend it. It will give you an insight you will not get from any guidebook and will help you engage in informed conversations about the situation out there, rather than just quoting misleading headlines.

*On a personal level, I had already decided before I read the book that I was not going to this World Cup. After waiting my entire adult life to go to a World Cup, Wales went and bloody qualified for a tournament I cannot condone. I read the book with an open mind though. Some of the book confirms previously held concerns, whilst some of it actually debunks a few myths. Overall, at the end I was comfortable with my decision to not go.